The Tragedy of Portland: ‘It’s a Ghost Town, Except for Zombies’

For seven months, Dylan Carrico Rogers slept in his bike shop with a shotgun. TriTech Bikes, located in the Montavilla neighborhood of northeast Portland, Ore., where Rogers grew up, had been battered by three break-ins, two nearby shootings, and countless instances of vandalism. Portland’s serially understaffed police force was nowhere to be found. And in the face of $25,000 of stolen bike parts, TriTech’s insurance company was ready to jump ship. “They said, ‘if you claim another one, we’re just gonna drop you,’” Rogers told National Review. “So I’m paying $1,200 every three months to be told that I have to replace [everything] on my own dime. And then at the same time, the cops don’t show up. So we’re just in a free-for-all.”

The lifelong Portland resident finally packed up and left in August. By that point, he said, the building landlord “told me that it wasn’t worth it anymore.” The graffiti, property damage, constant break-ins, and unattended-to police reports were just no longer worth the investment. “He tore up a three-year lease. The building’s vacant now,” Rogers said. The gloomy metropolis of 660,000, perched at the northwestern tip of Oregon, is not quite the anarchic dystopia that it is occasionally made out to be in some corners of conservative media. But in the wake of spasms of political violence, a slashed law-enforcement budget, a wave of early police retirements, and punitive lockdown measures that have devastated small businesses such as TriTech, it’s inching ever closer to genuine lawlessness.

This is the Portland way of life. “You have people that are just blatantly taking advantage of the fact that there are no police officers,” Rogers said. “I mean, this has spread everywhere now. It’s not just the Portland bike shops. Grocery-store workers are getting attacked, because we have drug addicts that are literally walking in andThis is the Portland way of life. “You have people that are just blatantly taking advantage of the fact that there are no police officers,” Rogers said. “I mean, this has spread everywhere now. It’s not just the Portland bike shops. Grocery-store workers are getting attacked, because we have drug addicts that are literally walking in and doing these blitz raids.”

Portland’s approach to governance over the past two years has been a paradox: an unholy marriage of lax prosecution of real crime and draconian crackdowns against law-abiding small-business owners and citizens. The district attorney for Multnomah County, where Portland is located, declined to prosecute 70 percent of cases related to Black Lives Matter protests last year, and the Portland Police Bureau leaves 911 callers on hold for hours. The city surpassed its all-time annual record for shootings in late September, with three months left to go in the year — and as is often tragically the case, black Portlanders were killed by shootings at twelve times the rate of white Portlanders. After the municipal government effectively stopped enforcing vagrancy laws, the homeless population exploded from about six large encampments to over 100. At the same time, Oregon has consistently led the country in public-health restrictions throughout the pandemic, with Governor Kate Brown routinely forcing businesses to close at unpredictable intervals, even after vaccines became widely available. Oregon’s outdoor mask mandate — which applied to vaccinated and unvaccinated residents alike — was the last remaining in the country, until it was finally repealed at the end of November.For business owners such as Rogers, the double whammy of arbitrary lockdowns and unpoliced crime is often too much to bear. “You’re seeing more and more people pull out,” he told National Review. And in turn, “when people like me and other business owners close up, and we leave, then you have no economy — and everything continues to get worse.” That civic spiral is clearly reflected in the economic numbers: Almost 260,000 Oregonians overall — close to one in eight members of the statewide workforce — lost their jobs in the first month of lockdowns alone. Perhaps most worryingly, job losses were steepest in the hospitality-and-leisure sector, which halved its workforce in the first two months of the pandemic. Restaurants, bars, and hotels are arguably Portland’s most important industry. But as of March, a full third of the sector’s lost jobs had not returned, likely as a result of the fact that downtown saw an 80 percent decrease in foot traffic.

“That’s what Portland has become,” said Rogers. This is how things went down, leading to his business’s permanent closing in August: “I have to sleep in my shop with a shotgun and do what the police were supposed to do, because there’s not enough police. I will be punished for doing what the police need to do if someone breaks in. But if I don’t do that, I’ll lose my business — because if someone breaks in, I can’t afford the insurance. You’re in a no-win situation. So why have a business at all?”

The adverse effects of Portland’s less-than-competitive economic policies have long been mitigated by the city’s crunchy charm: Set against the backdrop of snowcapped Mount Hood, populated by lovable kombucha-brewing oddballs and eccentrics, and repeatedly ranked as the top city in America for food and drink alike, the unique allure of Portland’s happy-go-lucky grunge on either side of the Willamette River has made it a target for investors and a magnet for tourists. But the Rose City’s culture and natural assets are no longer enough to balance out the effects of lockdowns, runaway homelessness, crime spikes, and general civic breakdown.

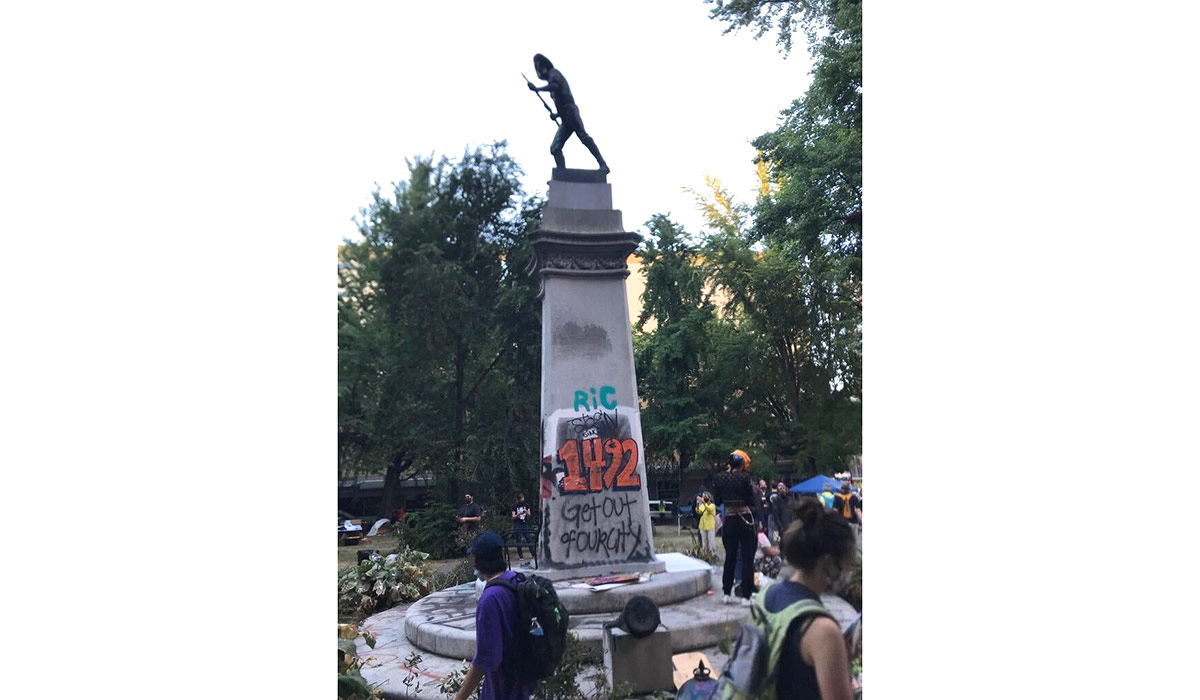

In 2021, Portland was downgraded from third to 66th out of the 80 most desirable cities for prospective investors and developers — the direct result of the reputational damage that the city has suffered over the past year and a half. While the riots that rocked Stumptown in 2020 were mostly confined to a few blocks surrounding the Multnomah County Courthouse downtown, their consequences are felt across — and beyond — the city. Large-scale demonstrations began to peter out by the end of August, but only after months of breathless coverage in the national media and an untold amount of economic damage. (The first four weeks of rioting alone cost the city some $30 million.) At the same time, Portland’s partially defunded and thoroughly demoralized police force seems unable to prevent the vandalism and destruction that a smaller posse of determined Antifa-style anarchists have continued to carry out in the months since. The city is gripped by a sense of helplessness — as if disorder and breakdown are an inevitability.

These recent developments have mostly gone unnoticed in the national media. Portland’s flirtation with political violence was given wall-to-wall coverage in the summer of 2020, but the media largely lost interest in the wreckage that Black Lives Matter riots left in their wake. Decline does not make for attention-grabbing headlines: It is a slow, uneven process, more of a whimper than a bang. More than anything, today’s Portland is a sad place; even setting aside the shootings, robberies, and break-ins at night, one has only to glimpse the boarded-up shops and once-beautiful river walks covered in homeless encampments, to smell the stench of cheap weed, or to witness the mentally ill transients roaming empty streets in once-vibrant neighborhoods to feel the sorrow of it.

This, in other words, is the face of a decaying city. “If you go downtown, it’s a ghost town, except for zombies that are walking around pushing carts because they have nowhere else to go,” Rogers said. “There’s no signs of life, except for these junkies — they’re the only people that occupy it. There’s no real business being done in downtown anymore.”

The most tragic thing about Portland’s sorry fate is just how avoidable it was. The city’s decline is a policy decision — or more specifically, a series of policy decisions, leveled on the working and middle classes by powerful activist groups and feckless politicians insulated from the real-world consequences of their acquiescence. In the burst of utopian ideological fervor that swept the city in 2020, Portland slashed its police budget by $15 million, disbanded three of its units — public-school policing, TriMet (the commuter bus and rail system) policing, and the Gun Violence Reduction Team — and cut eight of its Special Emergency Reaction Team positions. When the predictable consequences of those policies led to mass resignations in the Portland Police Bureau, the city government scrambled to restore the funds it had cut a year before, but the change of heart was too little, too late. Amid its worst staffing shortage in decades, PPB can no longer find officers to hire; Portland currently has fewer cops on the street than at any point in the last three decades. In an exit interview, one of the countless officers leaving the city put it poignantly: “The only difference between PPB and the Titanic? Deck chairs and a band.”

There is a sense that city officials have lost control of the forces they unleashed in summer 2020. Mayor Ted Wheeler initially defended the BLM protests, in fact praising them as part of Portland’s “proud progressive tradition.” In an open letter responding to then-president Trump’s offer to send federal law-enforcement agents to protect the city at the end of August 2020, Wheeler wrote: “On behalf of the City of Portland: No thanks. We don’t need your politics of division and demagoguery. Portlanders are onto you.” Today, an exhausted-looking Wheeler is striking an altogether different tone, declaring a state of emergency in April and saying it was time to “unmask” Antifa and “hurt them a little bit.” But what Wheeler fails to understand is that he is no longer in charge. The mayor himself has been the subject of repeated attacks by local militants and was forced to move out of his apartment when rioters set fire to the lobby. One gets the impression that arsonists and looters are mocking city authorities: When the ten-foot fence surrounding the downtown courthouse was removed in March, it took less than seven hours for about 100 black-clad arsonists to break its windows and set it on fire again. The fence went back up two days later.

I was raised in Rose City, and I will always love it dearly, but it is no longer the city that I grew up in. Contemporary Portland is a city of dreams deferred; it is filled with people like Dylan Rogers, a twice-homeless Portland kid who built a business from nothing, saw it destroyed in a matter of months, and is now unable to find work that pays more than $20 an hour — even as panhandlers on the streets pull in upwards of $150 a day. Now, in his free time, Rogers works with disabled kids. “That’s fun to me,” he said. “It matters to me, to go help these kids. Because Santa Claus should live longer than we allow him to. But this city — this city destroys Santa Claus early.”

No comments: